Since demolition crews at the Cook County Jail began to tear down two centuries-old dormitories “piece by piece”, Natividad Martinez’s eyes have been inflamed. The clunking sound of heavy machinery, falling debris, and hissing water cannons attempting to contain dust signals to residents like Martinez, who lives one block away, to stay indoors. By six in the morning, she tends to her small garden just outside her apartment, but by seven she is inside and won’t resurface until the next day.

She boils chamomile on her kitchen stove and stores it in a plastic container to chill for a few hours. Then takes out another plastic container that was prepped the day prior, soaks a cloth with the herb to clear her eyes, and repeats the process every day.

It helps, she says.

Hot or windy days are especially difficult to stand outside since demolition began. Air monitoring data provided by The Cook County Building Assessment Management shows a consistent reading of particulate matter 10 (or visual pollution) at the site; Only spiking well above the federal standard for short periods of time.

The air samples use a roughly 6 am to 4 pm metric than the federal 24-hour standard. This means that a full picture of the potential risks is left unrecorded. But some risks are known: Visible pollution might cause some discomfort, but smaller pollution (particulate matter 2.5) is invisible to the naked eye and often accompanied by its larger counterpart, and can make it into the bloodstream and is typically “associated with things like heart attacks and deaths.” said Brain Urbaszewsk, director at the Respiratory Health Association in an interview with our collaborators at City Bureau.

.Indeed, standing outside for just a few minutes feels like getting caught by a sandstorm. One can’t make out what is in the air but the eyes become irritated and blink rapidly as if something is caught in them. Prolonged exposure to this or any form of dust can create serious health concerns, says Dr. Shelby Hatch, a chemistry teacher at Northwestern University.

“None of it is good,” she said

Martinez describes her vision as a lenslet. It is like seeing two images of the same person. “The dust is what bothers me the most because I feel like I have garbage inside my eyes, and they puff up a lot,” Martinez said in Spanish. “I have always had puffy eyes, but now, with the [demolition], it is worse.”

Watching his mother struggle with respiratory issues, Gabrielle Ibarra, Martinez’s eldest son, is reminded of his history of asthma. “As a kid, I used to use the inhaler.” he said, “I remember there was oil everywhere and grease. Now I'm very sensitive to my eyes. Like, I'm constantly crying, cleaning them because I like sitting out here. We are always outside, and you do feel a little roughness in the throat, coughing, or maybe even breathing a little bit heavier.”

The demolition happening one block away at The Cook County Jail is only adding to the pollution that the neighborhood’s 75,000 inhabitants have endured throughout a given year. Residents have had to rely on creative solutions to cope with the air quality. Which is also at risk of becoming even more burdensome as an increasing number of distribution centers are planned in the next few years. Bring freight traffic and diesel pollution.

In collaboration with the National Geographic Society and City Bureau––a civic-journalism lab in Chicago––this story provides a visual document of the toll of poor air quality and stress in Little Village from 2020 to 2022. We use annual cumulative impact data and available data that measure pollution by the hour to track and document its effects on residents.

Natividad Martinez in her Little Village home

Cook County

There are two sides to the iconic arch on 26th street. One that faces downtown Chicago and the other that leads in. Both sides display the words “Bienvenido a Little Village”, or “welcome to Little Village”, on a metal banner. Constructed in 1990 by architect Adrian Lozano, the arch was meant as a gateway for the ‘The Mexican Mecca of the Midwest and the city’s second-largest revenue generator strip––26th street. Yet for decades, the community has been encircled by a web of railroad tracks. Freight trains, trucks, local traffic, and the harsh smells of diesel fumes and oil is a part of life.

The Latino immigrant, mix-status, multigenerational, and predominantly working-class community is well aware of the conditions surrounding them. In many households, there is at least one member or known family associate who struggles with a severe respiratory illness, like asthma.

The highly dense area neighbors a 1,252-acre industrial corridor (The Little Village Corridor)–– one of the most important manufacturing and distribution hubs in the country and the second corridor to undergo dramatic changes in the city’s industrial infrastructure.

The first, North Branch, in the city’s wealthier Goose Island neighborhood, went from manufacturing steel to post-industrial creative office spaces through rezoning ordinances and an Industrial Modernization Plan introduced in 2018. Then-Mayor Rahm Emmaunul, responding to the four aldermen who voted against the rezoning ordinance said, “we figured out a way to take an area and make it work for the entire city, not just one neighborhood or one part of the city.”

Yet the policy forced many industrial manufacturing companies that have outlived their usefulness to close or relocate in “receiving corridors''––industrial zones with little to no zoning restrictions like in Little Village. These corridors typically surround Black and brown communities from Oakland to Chicago to New Jersey.

In a Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy, titled A Case for Reforming Chicago’s Zoning Law, Charles Isaacs writes: “Across the various procedures for rezoning decisions...the Chicago’s zoning code fails to provide substantial stipulations for community engagement, environmental justice analysis, or basic transparency of information to support environmental justice communities like Little Village.”

The lack of zoning regulations and its close proximity to the I-55 Stevenson Expressway, the Chicago Shipping Canal, major freight yards, railroad tracks, and the neighboring large populations has made Little Village a top candidate for distribution centers.

The revitalization plan for the area has remained in “draft mode” since its inception but that hasn’t stopped companies from condensing in the area, according to employment numbers from the Department of Planning and Development. Its purpose is to maintain and expand “existing businesses and [attract] new businesses''.

Jose Acosta, Environmental Planning and Research Organizer for LVEJO (Little Village Environmental Justice Organization) said he expects big projects in the coming years.

“This last-mile logistics conversation is important because you can see these companies, they don't want to be out in the middle of nowhere anymore because it still took them too long to get into the city,” Acosta-Córdova explained. “They want to be closer to where they can promise people next-day delivery or same-day delivery.”

Residents have also expressed concern that the increasing number of distribution centers would mean more freight traffic and diesel pollution in the area already burdened by the worst air quality and other social vulnerabilities, according to a 2018 reform report by the National Resource Defense Council and the city’s own 2020 air quality report.

Kim Wasserman, Executive Director at LVEJO, says it's typical capitalism at work. “It just goes to show when outside developers and people who don't care about your neighborhood don't have a true understanding of what [these spaces] actually stand for,” she said in an interview in 2020. “It's just property, for them, it’s just real estate. And in a neighborhood like ours, it's so historically rooted. But also, once again, it’s a look into how our community's voice is viewed”

Socioeconomic disparities including unsafe living conditions, increasing monthly rent, linguistic barriers, and low and hourly wages, to name a few, have contributed to the area's stress count. These economic hardships have made addressing immediate health concerns more difficult.

“I believe in climate change and all that,” said Desiree Salazar, a longtime resident, and food vendor. “But I see my people struggling ––the warehouse will bring jobs and that’s what's important to me right now.”

Among the long list of social roadblocks, none have been more misused than the categorization that both hail and discriminate against the community in Little Village. Terms such as“the strong labor pool” or “the essential worker” have taken a double meaning in the last few years.

At the heart of the Industrial Revitalization Plan lies a global entity, Hilco Redevelopment Partners. When the company proposed a mega-distribution center at The Little Village Corridor, promising thousands of additional jobs in 2018, the project was placed on a political fast track. “The Hilco Redevelopment team understands that we have a terrific labor pool that can support the type of ‘new economy’ businesses that they expect...” said then-alderman Ricardo Munoz, who was later indicted on federal charges for misusing political funds to pay for personal luxuries.

The project, named “Exchange 55”, would replace the Crawford Station––a coal power plant linked to 48 premature deaths and 2,100 asthma attacks every year before its closure in 2012.

Environmental advocates and residents say that the project just replaced one polluter with another. They asked for a full evaluation of the site before any demolition work and later that 50% of jobs go to residents––the area where unemployment has nearly doubled that of the national average in the last decade.

None of the demands were met.

Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey. 1987. Library of Congress. Photos by Jet Lowe.

In 2019, Hilco was supported with a $19.1 million dollar tax break by city officials, under the condition that a physical facility was built and a leaser established.

“That’s the difference, ” said Jorge Cantu, who grew up one block away from Crawford Station. “[Elected officials] always put [distribution centers] here because they know they’ll get less of a bark. You have wealthy communities able to put up a fight because they have more resources and time to address these issues. Those neighborhoods would [be able to] stop it unlike over here, people are too busy working. You have your community leaders and all that but it’s not enough because eventually, these politicians have their own goals and money in mind.”

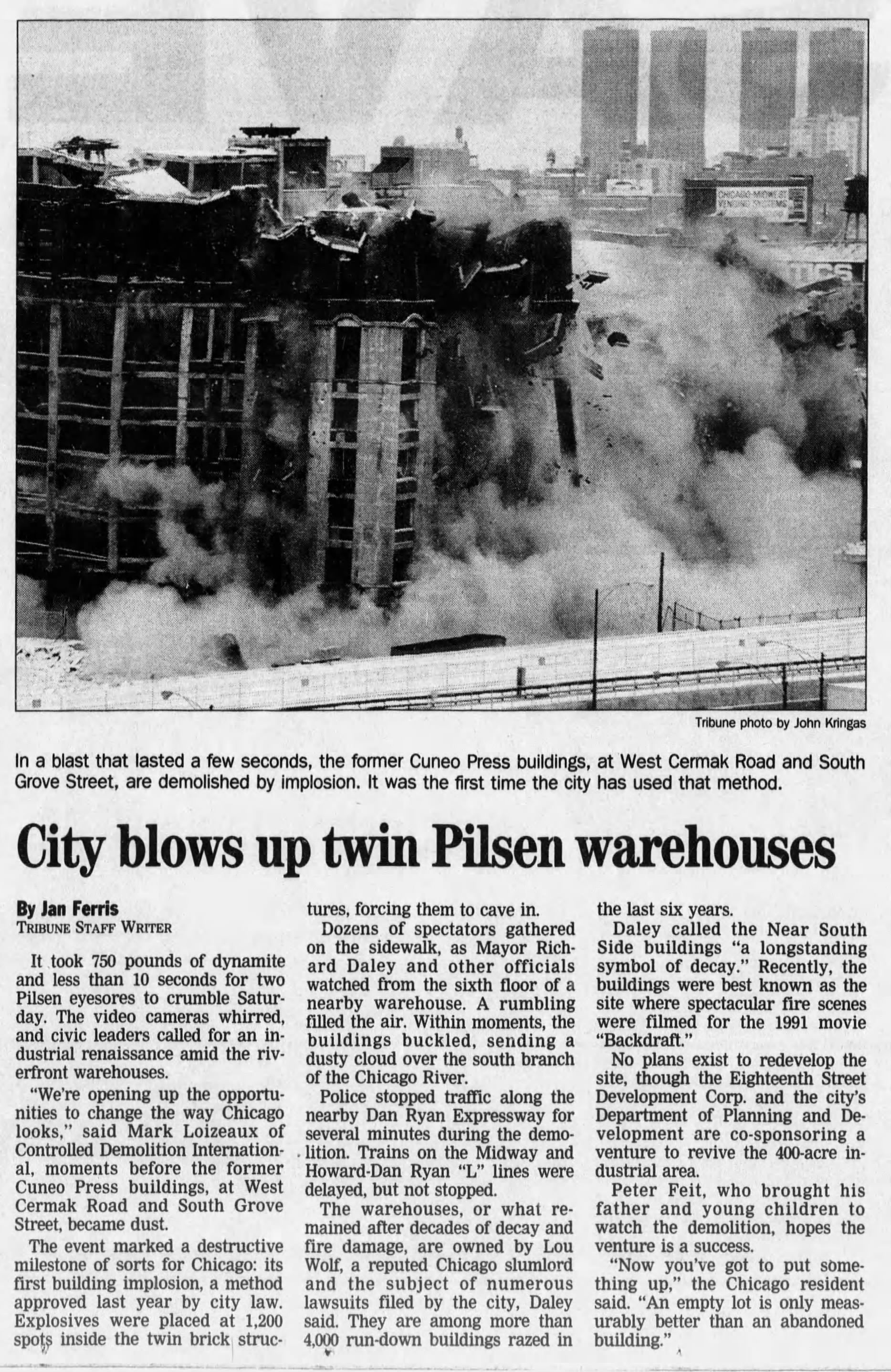

On Easter Sunday in 2020, a few weeks into the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hilco wasted no time to meet its deadlines. The company imploded Crawford’s 100-year-old smokestack tower using explosives––a practice the city hadn’t approved since the ‘90s when officials rid the city of its abandoned buildings and housing projects.

The implosion, overseen by Hilco, The Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH), The Department of Building (DB), MCM Management Corp., and Controlled Demolition Inc.--covered nearby homes, cars, and sidewalks in toxic dust.

With little notice, residents described being awakened that morning by two loud explosions: One when the TNT pushed the tower into a freefall, and the other when it smashed on the ground. In a video documented by a freelancer and circulated throughout the city with headlines reading We Just Want to Breathe and Lack of Disciplinary Action Against Hilco Over Botched Implosion, a large dust cloud can be seen quickly making its way past the railroad track that separated the corridor and the densely populated area.

contributor Alejandro Reyes

Antonia Quiñones Peña, a resident who lives near the site, was recovering from the first strain of COVID-19 when she was awakened by the loud booms. She remembers getting up confused and drowsy and quickly checking the kitchen and the bathroom, eventually looking out her window to see a large dust cloud coming towards her home.

“I was feeling better that morning and looked forward to taking my walks around the neighborhood again,” she said, “But then this happened and I couldn’t go outside.” Dust was everywhere, on cars and windows. “When it cleared eventually there was a smell so strong and heavy that it irritated my nose and eyes.” Quinones said, “It was horrible. I had never seen anything like that before.”

Jorge Cantu never saw anything like it either. Growing up one block away, he remembers the rumbling sound of coal being produced into energy but he never really gave it a second thought, he said. “I had always imagined [Crawford Station] would just blow up one day.”

His father, Fernando Cantu, was taking shelter on the day of the implosion. A few hours later, he passed away. The Cantu family believes that their father’s unexpected passing was the result of the implosion and lingering dust in the air, making him the second person whose death is associated with the project. “My dad loved going outside,” said Olga Ruan, Fernando’s oldest daughter. “So maybe visibility got better and [he] thought it was safe. If it was killing people before, imagine what it did to people now.” In reporting on this story, journalists discovered family ties with the Cantu family. Out of their request, we left out details of the night of his passing.

Three days after the implosion, a city investigation found levels of arsenic, barium, lead, NoX, and mercury in the soil around the site. An official statement says, “tests show no particulate levels considered to be unsafe for human health, per US EPA standard.” But, experts say it is

difficult to jump to any conclusions and if any of the pollutions was inhaled, it could cause serious respiratory issues.

Ground sampling was also done too late, says Sam Douravich, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Public Health in an interview with WNYC. “...you wait a couple of days [and] some of that chemical has already evaporated so you don’t learn very much about how bad things were initially...”

The City of Chicago responded to the botched implosion urging accountability for Hilco and their demolition partners. They would pay the majority of a $370,000 fine to the community stakeholder, Access Community Health Network, after the Illinois State Attorney filed a lawsuit stating the companies “failed to take steps to protect the community from air pollution” during a deadly respiratory pandemic.

Work continued throughout the year and well into the winter months. The modern gothic building that once stood as a reminder of injustice for many community members and environmental justice organizers vanished one piece at a time. It was replaced by a large cement box with loading docks and a few trees.

A year later, environmental advocates held a press conference near the site. Families joined mariachi bands to share their experiences of the implosion day and to remember loved ones who perished after decades of pollution. Some remember Fernando Cantu as a friendly neighbor, others a sweetheart always looking out for the young members he called Campeones (champions) of the community. Others noticed a shift in behavior and expressed concern over potentially developing asthma later in life.

In November 2021, Aldermen Michael Rodriguez (22nd) joined community council members and LVEJO in demanding full transparency over the mishandled implosion. He sent the mayor a letter with co-signatures from U.S. Rep. Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, state Sen. Celina Villanueva, state Rep. Edgar Gonzalez and Cook County Commissioner Alma Anaya, asking for the release of the Office of Inspector General’s report “as soon as possible”. The report calls for disciplinary action and a possible firing of three city officials involved.

The report was released in January, but no disciplinary action has been taken against those responsible.

When Target, now leasing the Exchange 55 warehouse, published 2,000 job openings with starting salaries at 18 dollars per hour, it meant that residents had an opportunity to address long travel times to work and make looking for childcare easier––two leading issues affecting workers today. But qualified Spanish-speaking applicants say they haven’t received callbacks.

Alderman Rodriguez of Little Village, who was present during the Target ribbon-cutting ceremony, agrees that travel time to work and a consistent work schedule are some of the driving factors of quality of life. “Predictive scheduling primarily for Black and brown women, I think that's something that we care a lot about in our community,” Rodriguez said referring to his

co-sponsorship of the Fair Work Week Ordinance. “And something we're working toward heavily.”

He denied that any applicants from Little Village were deliberately turned away by Target based on linguistics. There have only been two jobs fairs in the last year, which attendants say was more like an “applications fair”. People gathered from all over the city, some to ask questions about the time lag only to fill out another application, and others gathered hoping to speak with a representative.

As of Aug. 31, 2021, roughly 700 of the promised 2,000 jobs have been filled, according to Target. 112 are from Little Village. But many are still waiting to hear back. While others continue to work long hours some 40 minutes away. The general saying of endearment among workers reporters has spoken to: Poquito a poquito se llena el cantarito (Little by little the jar gets filled).

After losing her job at a local dispensary due to the covid-19 pandemic, Maria Figueroa, a single mother of six, started her own food business as a vendor on the main shopping strip on 26th street. Her children, all of whom struggle with asthma, some more than others, help their mother.

take on the thorny duty while she takes breaks to make calls from customers and doctor’s appointments.

In the first weeks of the pandemic, her children began attending school remotely. This made it difficult to find another job. But Figueroa was determined to make as much money as she could in case she died from the virus, she said.

“I’ll keep selling nopales,” she said, shrugging her shoulders with half a smile, “‘poquito a poquito se llena el cantarito’ that’s what we told ourselves this entire time...Now, I have to maintain this business if I want to keep gaining money from it. If I get another job, I'll be losing money. I don’t get up early anymore because my other jobs drain me. Going back and forth caring for five children, it’s [exhausting].”

This year was special for her eldest daughter, Estrella, who was turning 15-years-old––a special time for young Mexican girls. Figueroa worried she couldn’t afford to buy her a quinceañera dress and contemplated canceling the event or having a small party on the corner of 26th street.

Roaming an online Facebook group supporting single Latina mothers, she asked for help. Her community heard the call and donated a space, invited guests, Figueroa bought the drinks and food and her godmother provided the dress. “At first, we weren't going to do anything.” she said, “[Estrella and I] were thinking about how we can pull off her 15th birthday. My friend told me ‘don’t be like that, to do something even if it’s just a little dinner with her friends. Quince is a special day for little girls––for women.’”

A few months later, in winter, Maria can is still selling nopals on 26th street. I followed up with her recently to talk about factory jobs. Working at the factories isn’t something she’s interested in doing, she said. She gets by with what she makes selling nopals on the commercial strip. “The summer is coming and I would have to be up and ready before everyone else because others would win my spot,”

Her children also get sick a lot and the youngest of the six, just 5 years old struggles with asthma and frequently asks to be sent home from school. “That’s also why I’m not interested in factory work right now because if [the school] calls me, all I need to do is pack my things and let’s go!”

In recent months Maria's worries added. Her youngest daughter's father had passed unexpectedly and so did the financial support he provided. Her car was totaled by a drunk driver and broke Estrella's arm. The recent surge in gun violence injuring children was enough to stop her from bringing her own children to 26th street. “Everyone that comes out to vend feels the same way I do,” she said. “Even though it’s at night, the violence has become heavy. But you have to keep going out there in order to sustain yourself. Without fear you need to keep doing what you’re doing.”

This collection of photographs is permanently archived at The Library of Congress

Supporters:

National Geographic Society, City Bureau, SouthSide Weekly

Reporters:

Ata Younan, Leslie Hurtado, Ger Salgado

Contributors:

Alex Arriaga, Alejandro Reyes